On Wednesday, January 6, 2021, a throng of insurrectionists attacked the U.S. Capitol in a failed effort to overturn the results of the 2020 election. Hundreds of rioters aggressively marched toward the Capitol to protest outside and break into the building. In the process, they harmed police officers and vandalized and looted while they sought to find and harm members of Congress. The riot led to the evacuation and lockdown of the Capitol and caused several deaths and injuries. While many aspects of Jan. 6 were unprecedented, others are uncomfortably familiar. If we place the Capitol riots in the context of the American Civil War and the violence from that era at the Capitol, we see a repetition of history that begs the question what, if anything, have we learned?

From the burning of the Capitol during the War of 1812 to the shooting on the House floor by Puerto Rican nationalists in 1954, the “people’s house” has attracted its fair share of violence–especially leading up to and during the Civil War, when fights between Congressmen was commonplace. In Joanne Freeman’s book, The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War, the 1830s through the 1850s saw numerous violent clashes over slavery between Northerners and Southerners on the House and Senate floors. While Congressional combat was common prior to those years, it dramatically escalated approaching the Civil War.

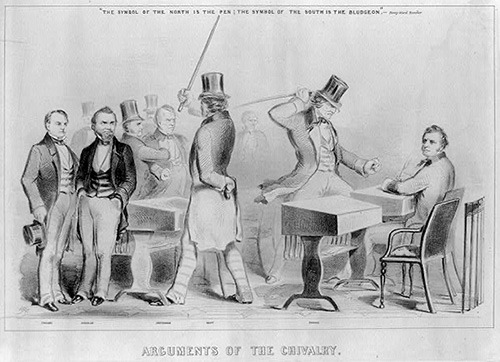

The most infamous example of this was in 1856, when Massachusetts Senator and abolitionist Charles Sumner was severely beaten by Representative and antiabolitionist Preston S. Brooks of South Carolina. Brooks was enraged by Sumner’s public remarks against his cousin, Senator Andrew Pickens Butler, and against Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas, both of whom also opposed the abolition of slavery. In retaliation, Brooks struck an unsuspecting Sumner with his cane half to death.

The most infamous example of this was in 1856, when Massachusetts Senator and abolitionist Charles Sumner was severely beaten by Representative and antiabolitionist Preston S. Brooks of South Carolina. Brooks was enraged by Sumner’s public remarks against his cousin, Senator Andrew Pickens Butler, and against Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas, both of whom also opposed the abolition of slavery. In retaliation, Brooks struck an unsuspecting Sumner with his cane half to death.

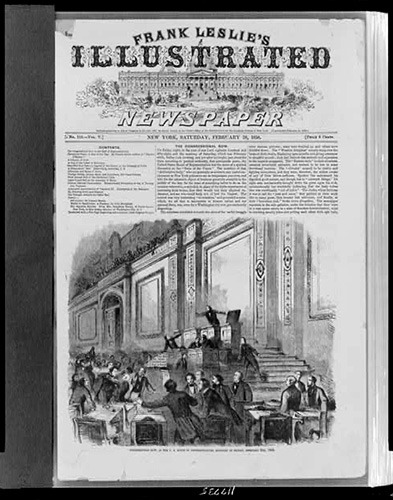

Similarly, in 1858, while debating the Kansas Territory’s pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution, arguments grew heated between Northern and Southern Congressmen, resulting in a physical brawl. The fight only ended when Republicans John Potter and Cadwallader Washburn ripped the toupe off the head of William Barksdale, a Democrat. Although the spectating Congressmen dissolved into laughter as the fight ended, it stood as a symbol of the nation’s increasing divisions. While studying these violent incidents, Freeman noted that “when fighting became endemic and Congressmen strapped on guns and knives before heading to the Capitol every morning – when they didn’t trust the institution of Congress or even their colleagues to protect their persons – it meant something. It meant the extreme polarization and breakdown of debate. It meant the scorning of parliamentary rules and political norms to the point of abandonment. It meant the structures of government and bonds of Union were eroding in real time” (Freeman, xxiii).

The January 6 Capitol insurrection was therefore unusual in its execution and magnitude, not its occurrence or origins. While Capitol violence has at times been commonplace, only the burning of the Capitol during the War of 1812 can come close to the size and scope of the January 6 attack–remarkable considering that the former was during war with a foreign enemy.

Further, the divisiveness, anger, and white supremacy expressed by insurrectionists on January 6 is similar to the attitudes of pre-Civil War Southerners in their defence of slavery and opposition to the election of Abraham Lincoln before they seceded and fought against the Union. The South did so to maintain a system of racial inferiority and enslavement that benefited their way of life. Similarly, those who stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6 feared a loss of power and acted with violence to protect their own way of life. On January 6, the scenes of black officers being chased by angry white protesters, some bearing a Confederate flag, is a dark reminder that racism and white supremacy still persists in the United States, more than one and a half centuries since the conclusion of the Civil War.

Further, the divisiveness, anger, and white supremacy expressed by insurrectionists on January 6 is similar to the attitudes of pre-Civil War Southerners in their defence of slavery and opposition to the election of Abraham Lincoln before they seceded and fought against the Union. The South did so to maintain a system of racial inferiority and enslavement that benefited their way of life. Similarly, those who stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6 feared a loss of power and acted with violence to protect their own way of life. On January 6, the scenes of black officers being chased by angry white protesters, some bearing a Confederate flag, is a dark reminder that racism and white supremacy still persists in the United States, more than one and a half centuries since the conclusion of the Civil War.

But while history provides us context to the events on January 6, it cannot predict what will happen next. As we continue to move toward a more perfect union for all Americans, we can hope lasting change is made. To do so, though, will first require us grappling with the root causes that brought violence to the Capitol’s halls, both during the Civil War and today.

Written by guest contributor Taylorann Vibert, a Senior at the University of Maryland studying both History and Government & Politics.

Sources:

Cramer, Maria. “Confederate Flag an Unnerving Sight in the Capitol.” New York Times. January 9, 2021.

Freeman, Joanne. “The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War”. (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, Sept. 11, 2018).

Givhan, Robin. “Flying the flag of facism for Trump.” Washington Post. January 6, 2021.

Leatherby, Lauren. “How a Presidential Rally Turned into a Capitol Rampage.” New York Times. January 12, 2021.

“The Most Infamous Floor Brawl in the History of the U.S. House of Representatives.” Office of the Historian, U.S. House of Representatives.